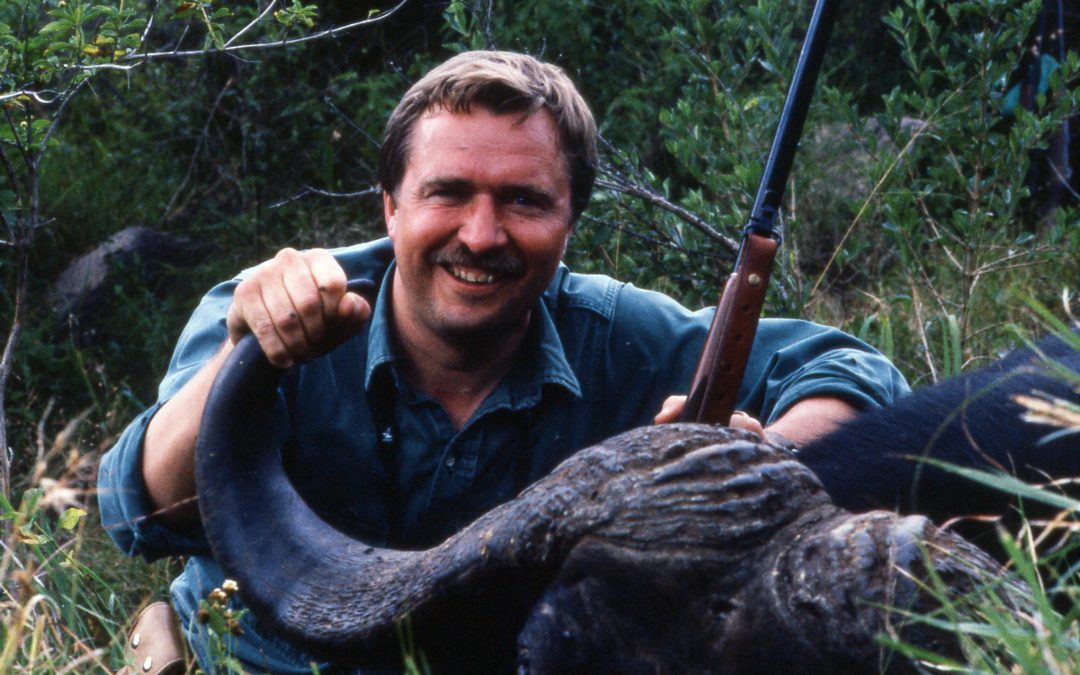

Wieland with his Mount Longido bull – a Cape buffalo that proved the legends to be true.

By Terry Wieland

Years ago, I was told that professional hunters in East Africa wanted a young PH to have a close call with a Cape buffalo early in his career. Why? Because, they said, you could hunt and kill 500 buffalo without incident, become complacent, and number 501 would get you. Better to learn a lesson early.

Recently, a writer I know and respect, who has hunted all over the world, including many Cape buffalo, wrote that he did not know, personally, anyone who had experienced a problem with a buffalo, much less an injury. Nor, he wrote, did any of the professional hunters he canvassed on the subject. Cape buffalo, he insisted, are over-rated. (In fairness, he later told me it was semi-serious hyperbole.)

Well, I beg to differ, and I would like to point out that his statement about none of his acquaintances is patently untrue, because he knows me, and in March, 1993, high atop Mount Longido in the Great Rift Valley of Tanzania, I had a problem that ended only with a bullet in a buffalo’s skull at four feet. Had that bullet — my third shot — not found its mark, I would probably have ended up dead.

A brief explanation: I was hunting with just my PH, Duff Gifford. Our trackers were eating breakfast by the fire while we scouted in the early morning. I found a big bull amid the brushy dongas on the mountainside, put a bullet into his lungs at 75 yards, and he dashed into a ravine. From up on the edge, we could see nothing through the brush but we could hear his labored breathing. If he did not come out in ten minutes, we decided, we’d go in after him. At ten minutes almost to the second, the bull came out at a run and up the trail on our side. He was hunting us.

At any time, he could have escaped down the ravine under cover. Instead, he lay in wait, facing back the way he’d come, with one purpose in mind: He was dying, I believe he knew it, and all he had left was revenge. He soaked up three shots, never wavering, before the final bullet dropped him.

Before that incident, I had killed two Cape buffalo; I’ve killed four more since, and been in on the deaths of a dozen others. Of them all, the Mount Longido bull was the only one that demonstrated mbogo’s legendary traits of vengefulness, determination, and cool ability to formulate a strategy and carry it out to the bitter end. But one example was all I needed, and I’ve never since questioned the legends.

Unlike the other notably dangerous game of Africa — lion, leopard, elephant — the Cape buffalo is a decidedly Jekyll-and-Hyde character. Most of the time, he’s a peaceful herd animal who just wishes to be left alone. Let him be angered, or wounded, or caught in a snare, or have a toothache, however, and he can turn into an enemy as calculating and dangerous as Doc Holliday.

What’s more, he’s not content just to rough you up and move on. Once the decision is made, he’s not happy until you are are reduced to a bloodstain in the dust.

In 2004, two men were killed by Cape buffalo, in separate incidents in the Rift Valley. Neither was hunting buffalo. In fact, Simon Combes, a wildlife artist of my acquaintance who had lived in Kenya his entire life, got out of his car to look at the view over the Rift when a bull came out of the bush and savaged him.

The other victim was a Canadian outfitter — an experienced hunter — looking for tracks around a waterhole. He was carrying only a .270. Again, a bull buffalo, and again, out of nowhere and for no known reason. Neither bull was ever found. Snare? Toothache? Old wound? To this day, no one knows.

If, however, you read that Cape buffalo are over-rated, oversized cattle without a malicious bone in their bodies, please keep the above incidents in mind. And when in buffalo country, carry a buffalo rifle.