One for the Road

By Terry Wieland

Time Spent in Reconnaissance

Many and lurid are the tales told by professional hunters of clients who show up with rifles they can’t shoot, of rifles not sighted in, even of clients so afraid of their rifles they have never even fired them.

Some years ago, I was told of a client who arrived in Tanzania to hunt Cape buffalo with a new .505 Gibbs. He had not shot it even once, and wanted his PH to sight it in for him. With recoil so fearsome, the client figured he could steel himself to pull the trigger once and only once, and he wanted that one shot to be at a buffalo.

Professional hunters can be forgiven if they view every new client with a jaundiced eye. Better to expect the worst and be pleasantly surprised than to view the client with sunny optimism and high expectations, only to find at the absolute wrong time that he’s a fool or an incompetent.

For a century, safari writers have been urging would-be clients to spend time at the range and practice with their rifles, and some (myself included) have even offered suggestions for types of targets, and setting up situations that simulate real life. If anyone ever took this advice, it would be a surprise to me.

One answer is a professional shooting school, and in recent years, any number of these have sprung up around the U.S. They purport to offer instruction in everything from long-range sniping, to house-clearing exercises, to dealing with an incoming buffalo at feet, not yards. Some of these are pretty good, although I would want to know the qualifications of the instructor.

Some evidently believe they’re on a Marine Corps drill square, and spout things like “I’ve hunted armed men, and that’s the most dangerous game of all!” Even assuming he’s telling the truth — and that itself is questionable — there is no direct correlation between the two except in the realm of psychology: In both instances, your life is in your own hands, and you have to get a job done in the face of a mortal threat.

No shooting school can simulate that. What it can do, though, is teach you gun handling to the point where you become completely confident in your own abilities. Calming self-confidence is a highly desirable element in dealing with dangerous game — or any game, for that matter. We were taught in the infantry that “time spent in reconnaissance is never wasted.” A good shooting school is a form of reconnaissance, and that old infantry rule holds true.

I must confess to some misgivings when, in April, I went to the FTW Ranch in the west Texas hill country to try out a new rifle/ammunition/riflescope combination. The FTW has an extensive facility for hunting and shooting instruction; what worried me was what I perceived to be its emphasis on shooting at long range — by which I mean, from 600 yards all the way out to 1,600.

The current craze for “long-range hunting” has its origins in the hero worship surrounding military snipers, combined with endless blather on television shooting programs. We can dispose of the latter pretty simply: television is essentially fraudulent, and the most pathetic display of shooting blunders can be edited to look like a spectacular one-shot kill. As for the military, the goals and methods of military sniping are totally different than those of a hunter, whether he has any idea of ethics or not.

There are two essential differences. First, today’s military snipers work in teams, while hunters generally work alone. A two-man team includes a shooter and a spotter, both highly skilled specialists.

The second difference is that a sniper is happy to merely wound his target, whereas a hunter wants a clean kill. A sniper has no obligation to follow up his quarry and finish him off, which requires close observation of how the animal reacts to the shot, where it was exactly when the shot was fired, then finding that spot and tracking it. The longer the range, the more likely the shot will stray from the kill zone to merely wounding, and hence the more critical this becomes.

One could add that there is a huge difference between the bullets used by snipers and those required by hunters. No one should hunt with a non-expanding target bullet, but having a sufficiently accurate bullet that expands reliably at virtually any range and velocity is a very tall order.

But back to the FTW. Owner Tim Fallon has hunted big game all over the world, as a glance inside the main lounge will show. The walls are lined with trophies from Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, as well as the Americas. Prominently displayed alongside them is a large sign that reads:

“It’s the hunter’s job to kill an animal instantly with the first shot. Hunters owe it to the animal to accomplish that. If not 100% certain, get closer or don’t shoot.”

In essence, everything that happens at FTW reinforces that dictum, not only to instill a sense of hunting ethics, but also to show the limitations of the shooter and his equipment.

“Our purpose, of course, is to make our students better overall shots,” Tim told me, “But we do not encourage shooting at long range.”

As Tim figures it, showing a student just how difficult it is to hit anything beyond about 350 yards will discourage, not encourage, wild shooting. Being a game ranch as well as a shooting school, they encounter the problem first hand.

“We have guys who come here to hunt, insisting they want to shoot at really long range. I tell them, sure, you can do that, but first you have to take your rifle to the 700-yard range with one of our instructors. If you can hit the steel plate at 700 yards on your very first shot, cold, then you can hunt the way you want. If you miss, you do it our way.

“In the years I’ve been doing that, not one single hunter has made that 700-yard shot,” he said. “Not one.”

The FTW’s ranges include a wide variety of both distances and target types. The 700-yard range has steel plates the size of normal kill zones for big-game animals from 100 to 700 yards; there is a short (40- to 100-yard) moving-target range; a 350-yard moving target range; and a dangerous-game walk through the undergrowth, in which hunters, accompanied by a “PH”, encounter different animals under different situations, but always striving for realistic scenarios. For example, in thick bush you do not see an entire Cape buffalo, only a part. Or, with elephant, shooting at one may cause another to suddenly appear, right on top of you.

Finally, of course, there is the ultra-long range, with targets as far away as 1,600 yards. Interestingly, after shooting for half a day on the 700-yard course, none of us had any interest in 1,600 yards.

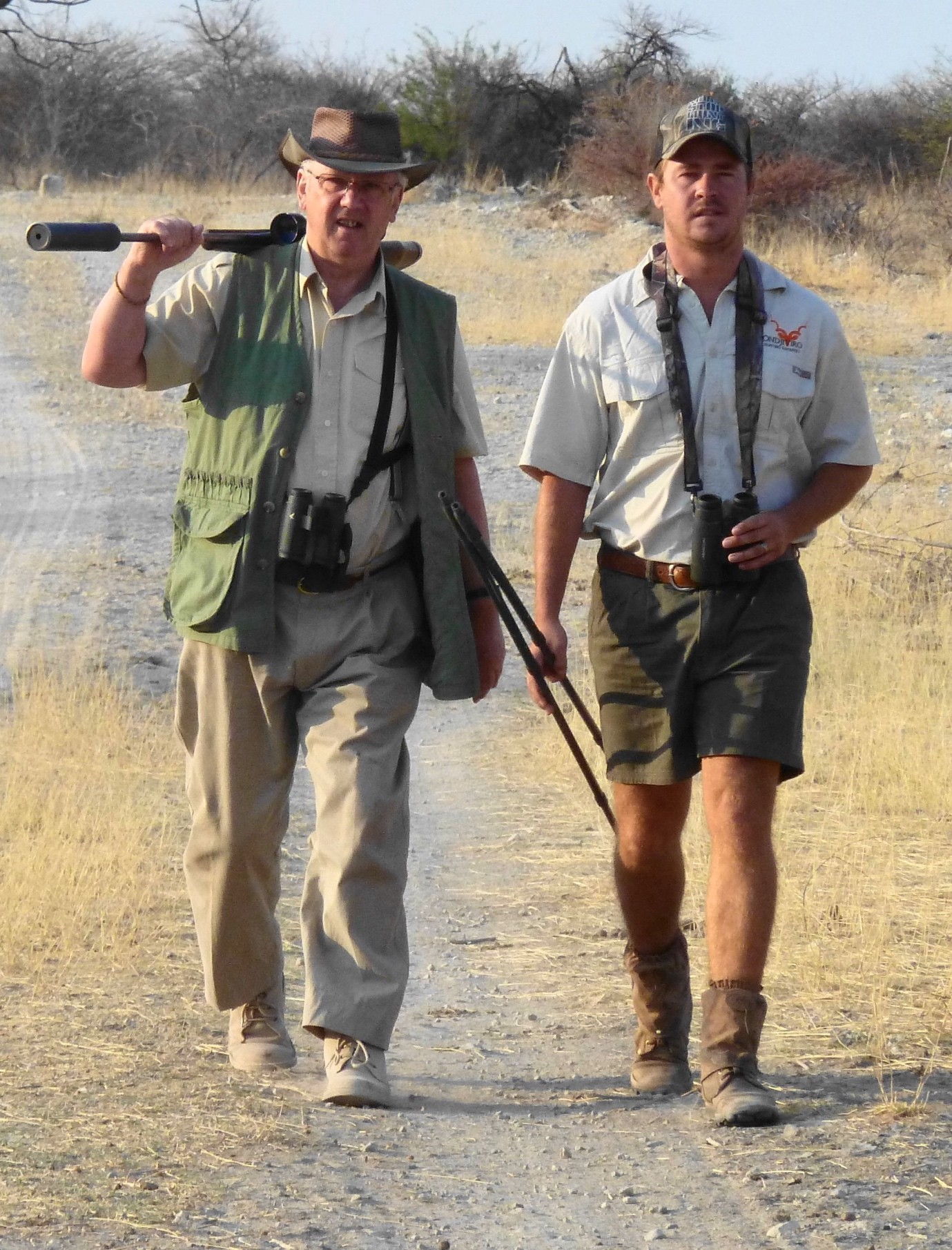

Tim Fallon’s team of instructors comes from a variety of backgrounds, mostly military, but unlike those I’ve found at other shooting schools, they don’t think they are still in the Marines. There is an air of relaxed professionalism about the whole place. And, for real-life situations like the dangerous-game walk and the 350-yard moving target, Tim consults real professional hunters.

“Every year, I invite professional hunters at the Dallas Safari Club show to come up for a few days, to see what we do, and make suggestions how we can improve,” he told me. “That has been invaluable. It’s why we are now able to put our students into situations, as with Cape buffalo, that come as close as possible to reality without actually having a live bull in the bushes.”

The 350-yard moving-target range deserves special attention, partly because I consider 350 yards to be, first, a long shot for myself, and second, the longest range at which the vast majority of hunters should even consider shooting. There is a covered area from which you shoot, prone, with or without a bipod or sticks. At 350 yards, there is a berm with a gap in the middle; in that gap is a frame hung with steel plates, either six or nine inches diameter. There is also a rail with a target that comes into sight from behind one side of the berm, crosses the gap, and disappears behind the other side.

The shooter is required to hit a steel plate (simulating a shot at a standing animal) which sets the moving target in motion. It can travel at different speeds, stop, reverse — anything a diabolical instrutor could desire. The idea is to hit the plate, reload, then hit the moving target. At 350 yards. If that does not give a hunter a realistic assessment of his own abilities and limitations, I don’t know what would.

I went there thinking 350 yards is a long shot. Although I hit the stationary plate with fair regularity, the moving target was something else altogether. I came away thinking 350 yards is a very long shot — for me and for most others. I guess Tim Fallon accomplished his mission.