One for the Road

By Terry Wieland

Lions, Kittens, and Cats

A first encounter with a wild lion is a life-changing event. It may not seem like much at the time. Both of you may walk away unscathed. But I defy anyone to eradicate the memory. It stays with you until you die. And, in truth, you hope it will.

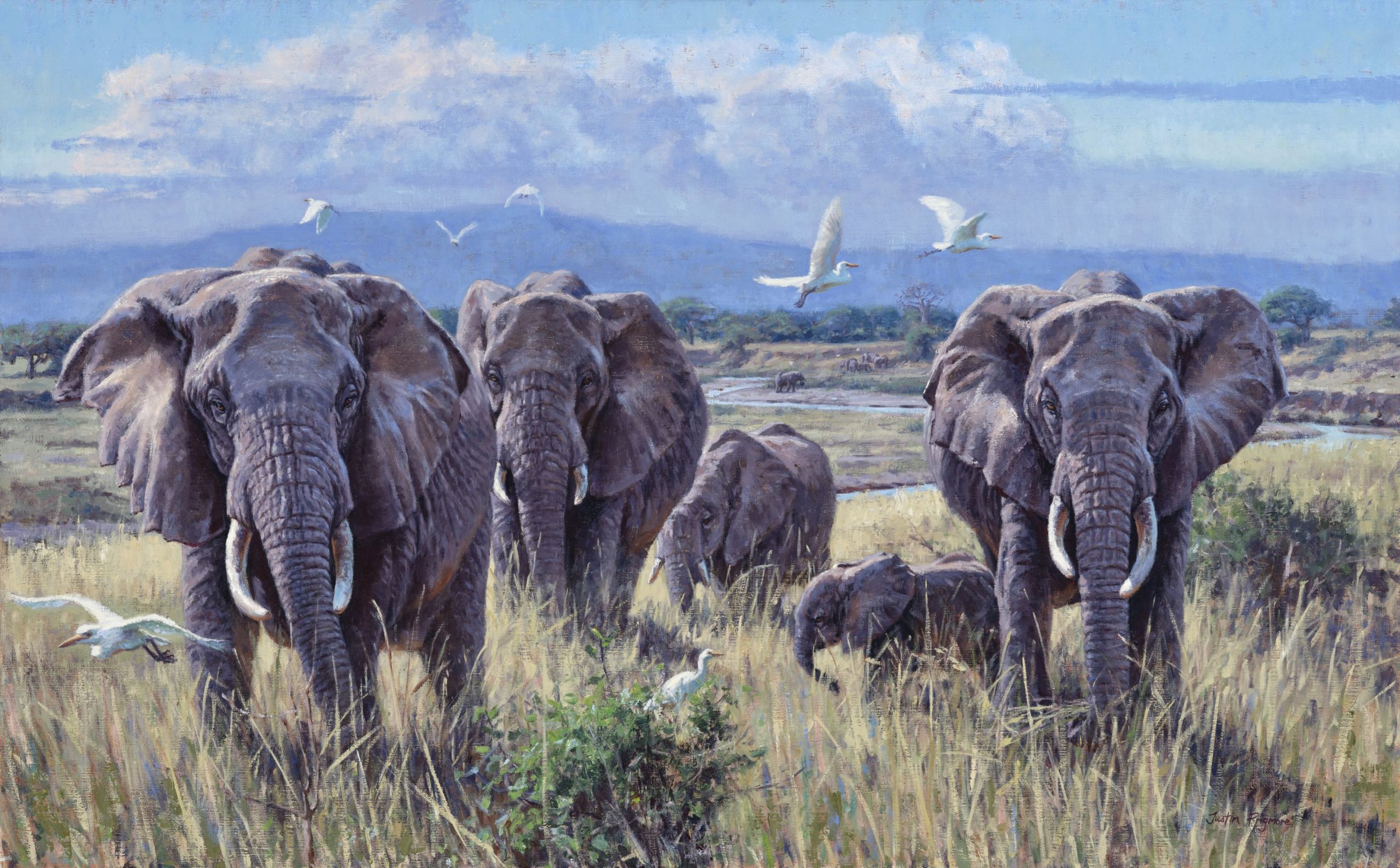

Of all the Big Five, lions hold a fascination for human beings that is mysterious and inexplicable. Everyone acknowledges it, but no one can put their finger on exactly why. There is no single lion trait that’s exclusive to the big cat. They can be man-eaters, but so can leopards; they form family groups, but so do elephants; they can hold a grudge against humans for no apparent reason, but so do Cape buffalo.

One big difference is that humans find lions almost universally admirable — at least, humans who don’t live among them, day after day and, more critically, night after night. Every time I’m tempted into a reverie about my experiences with lions, into my head pops the voice of a Tswana friend from years ago. We somehow got talking about lions. “Lie-owns are bad,” he said, shaking his head. “Ver’ ver’ bad.” Since he had lost a cousin or two to hungry lions, and I had not, it was difficult to argue.

Still, man-eating lions are rare, like the rogue humans who commit armed robbery. No one glorifies them, although the man-eaters of Tsavo gained world-wide notoriety and really put Kenya on the map. Bonnie and Clyde did much the same thing for east Texas.

Although I’d been to many parts of Africa, and spent the better part of year there, in total, since 1971, I never encountered a lion in the wild until a safari in Tanzania in 1990. Driving along a narrow hillside track, we came around a turn and found a pride of lions sprawled on the road. Robin Hurt was driving, and immediately hit the brakes. One big maned fellow looked at us calmly with his pale amber eyes, not 20 yards away. We backed up, Leo thought it over, and then rose and strolled into the bush.

Nothing really happened (although it certainly could have) except that, at that moment, any desire I ever had to hunt lions evaporated.

Like others of the Big Five, as well as the greater kudu, the lion has the power to fascinate, and some men become primarily lion hunters. J.A. Hunter was supposedly one such; Jack O’Connor, the American writer, was another. “I have hunted the lion,” he wrote proudly after a safari in the 1950s, and the fascination stayed with him. Robert Ruark, on the other hand, hunted lions but was really fascinated by leopards. Personally, I consider myself a buffalo hunter, and would hunt mbogo in preference to almost anything else.

Later on the same trip, hunting buffalo in the Okavango in Botswana, I had my second encounter with wild lions. We were tracking a herd of buffalo which had come to water during the night and withdrawn into the bush. With two trackers, my PH and I crept along, catching glimpses of black hide. For some reason, the buffalo kept spooking and thundering off. Sometimes, we knew they’d caught a whiff of us, but other times there was no explanation. Finally, they withdrew for good, leaving a cloud of dust hanging in the late-morning air as the sound of hooves faded to nothing.

Hot, tired, and thirsty, we began the long trudge through the sand to the hunting car, five or six miles back. We came to a clearing, one of the dry pans that dot the Okavango, and found, lying there, a lion and a lioness. The lady jumped to her feet, but the lion just raised his head and glared at us. He wasn’t moving. We backed away and circled well around. It all became clear what had happened. While we’d been hunting one side of the buffalo herd, they were hunting the other. We had taken turns ruining each other’s stalk.

I felt bad about it, as if the lions were somehow colleagues. We at least had the chop box in the safari car, whereas if they wanted lunch, they had to start over. No wonder he glared at us.

The most famous case of a white man being killed by a lion was George Grey, in 1911. Grey was the brother of Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign minister, during the Great War. He was hunting lions on horseback on a farm in the Aberdares, got too close (by his own admission later), and failed to stop a charging lion with his .280 Ross. The high velocity bullet has been blamed ever since but, before he died in a Nairobi hospital, Grey said it was his own fault.

Another famous story concerns Denys Finch Hatton, the well-known professional hunter and lover of Karen Blixen, who died in a plane crash in 1931. He was buried in the Ngong Hills, and it was said that for years afterwards, a lion would come and lie beside his grave, looking out over the plain.

Humans have a tendency to anthropomorphize lions more than other African animals, crowning him the King of Beasts, and writing cute stories like “The Lion King.” That is, when they are not living in fear. This gives our relationship with lions a contradictory duality, and results in the kind of pro-lion, anti-lion conflict that we see in North America with wolves. My old Tswana friend had no doubt where lions fit into the scheme of things, and wanted no part of them.

Generally, except for man-eaters, lions seem to treat humans, if not as equals, at least as something interesting but inoffensive. Willy Engelbrecht was a PH in Botswana who had a great reputation as a hunter of lions, but he also liked them. Willy hated sleeping in a tent, preferring to pitch a little pup tent away from everyone else, and heating his water for tea in the morning over a small fire. One morning, he opened his eyes and looked up through the mosquito net to find a lioness sitting there, calmly looking down at him. Their noses were about a foot apart. What did you do, Willy, I asked? “Lay as still as I could,” he replied. “What else was there to do?”

Sometimes, lions seem to like to tag along. Another PH friend of mine was clearing some roads in a concession up in Kwando, near the Caprivi Strip. They were sleeping under the stars, moving camp every day. One night, Chris woke up to find a lion sitting by the fire, staring into the coals. Just sitting there. Another time, he found a lion stretched out across one of his sleeping men, snoozing like a cat in a lap. The sleeping man was snoring away. The lion was just being sociable.

As tamers of lions have found, to their cost, over the centuries, taking a lion for granted, and letting down your guard, or forgetting you are dealing with one of the most dangerous and accomplished killers on earth, may be the last thing you ever do.

My last encounter was in a camp in the Okavango, the year before hunting was closed. There were lions all around — we’d find their footprints in the sand around our tents in the morning — and walking back from the campfire after dark was a little hair-raising.

One night, a herd of Cape buffalo took up residence just behind our tents, and we went to sleep to the gentle sounds of herbivores. Around one in the morning, we snapped awake to hooves pounding like thunder. The buffalo were being chased, and as the pounding faded, it was replaced by the sounds of a terrific battle — a buffalo bull, bawling and fighting for his life, and the roars of lions, all just a few yards away through the bush. We were painfully aware that we had nothing but a length of 12-oz. canvas between us and the Great Outdoors.

Finally, the battle ended, and we drifted off to the relatively peaceful sound of tearing flesh, crunching bones, and lions exchanging testy growls as they sorted out who would eat where.

As we later learned, there were six big male lions, hunting together. They used our camp as a screen, coming at the buffalo from between the tents in a long line, and brought down a big bull just behind my tent at the end. We drove out in the morning and found them in a clearing. Three were still eating, two were licking their paws and grooming, and one was lying on his back, all four paws in the air, sleeping it off.

We stopped the safari car and watched them. They looked at us, and kept eating. That was my last memory of the Okavango as hunting country, and I couldn’t ask for better.