Chapter Ten

The Ethics

The hunters found a track yesterday, shortly after noon, and followed it south towards the escarpment. It was a big elephant. His tracks indicated that he was old and had experienced some kind of mishap with his back left foot which, every now and then, when the elephant trod in the soft red dust, showed a scarred or raised ridge. For the first four hours the elephant did not stop. He did not feed and he ignored several clear trickling streams. He was, the hunters said, “on a mission”. But as evening crept in, the Zambezi Valley escarpment was no longer a soft blurred hazy blue. The tired group could now clearly make out the rock formations, individual trees and bush-thickened crevasses. Still the tracks headed south towards these hills, but now several shrubs had been ripped from the rocky soil and the bull had chewed on their roots as he walked. He was slowing down. The wind was still good, coming down off the escarpment and into the faces of the hunters but it was no longer heavy and hot, it was cool, and gentle.

The hunters found a small grassy basin protected from the wind safely out of any elephant road or buffalo trail, and they sat, exhausted, and drank water. There would be no fire tonight. No loud talking or laughter which could alert the elephant. They ate their cold sandwiches and as the now chilly breeze pushed the last of the sunlight over the edge, the purple then black of the African night fell into the valley and quickly the glittering stars came out. A hyena questioned up in the hills, but no one answered.

The American was both tired and sore. This was the twelfth day of his sixteen days in which he must collect his bull elephant. He had planned and dreamed and anticipated this safari for nine years. He had wanted it like some people want a new car, or a new house, or retirement. It was not so much that he wanted the elephants teeth, or his skin, or his feet, or tail. He wanted the experience. He wanted to experience the feeling, the adventure, the danger, the smells, the hardship. He wanted to experience the hunt. This man had an inner craving to tramp the trails of two hundred years past. He craved to endure, and satiate himself with a time of Africa that had slipped away into torn, sepia-toned photographs and nearly forgotten memories of adventure, and a kind of romance.

He had now done these things and was pleased. His guide and friend also loved these things and was also a part of them. He loved them but he also loved that be had been a part of this adventure before it could no longer be had. So he was pleased, and tired, but he was anxious too. The experience by itself, with no conclusion, was a half-full cup. There must be a conclusion. They must find the elephant and the hunter must take the life of the elephant if his tusks are big enough. If he is old enough. Or, the hunters may see that the elephant has old broken tusks and is of no value to them as a trophy, and they will let him go on his way.

So actually, the teeth of the elephant are the important thing, really. Or are they? What is the mark, or the reward, or the measure, of this hunt? Whether the beautiful teeth of the elephant ring the stone fireplace or whether they remain in the aging head of the beast matters not to the experience of the hunt, which has been full and perfect. So why the anxiety? How will the hunter feel really, when he has spent twenty thousand hard-earned dollars, and has walked hundreds of rough hot miles in the wilderness and goes home empty-handed with experiences only? Will he feel complete? Or will he feel let down, disappointed, and short-changed in some way?

Why does he want the teeth of the elephant to be big? The elephant is old, with a very large body. The hunters say that they strive to, and pride themselves in culling the old, past-breeding bulls who are approaching the last trek in life’s walk. So why do they care, or place emphasis, on the beauty or weight of the teeth? Is it recognition they are seeking – a little bit of fame will now come the hunter’s way if the ivory is heavy? Is it because he will be able to ignite admiration, or envy, from his peers? Does he think that he will be a different, better man if he shoots an elephant with eighty-pound tusks than if he shoots one with thirty-pound tusks? If the truth is, like he says, that the hunt itself is the reward, why does he care whether the tusks are old and broken, or if they are old and long? The hunters huddle down in their sleeping bags and look up into the night and the American whispers.

“How far ahead do you think he is”? The professional hunter laughs quietly. “Who knows? He has walked hard and straight for six hours. I think he was headed for the escarpment for a reason. I don’t think he is spooked. His dung has not been loose, and dropped and scattered whilst running. The wind has been good. Maybe he knows of a secret tree, a place where something has come into fruit. Sometimes, elephants just pack up and go. Who knows the reason? Tomorrow, hopefully, we will find out. Go to sleep”.

But he did not sleep. After all these miles, not only today, but for the last twelve days, after all these miles, will he shoot an old, broken-tusked thirty pounder? The trophy fee on the elephant is a further twelve thousand. He has already spent twenty. “Shall I spend twelve thousand to pull the trigger for part of a second?” “Should I count my blessings and be thankful that for twenty thousand I have given myself this fantastic experience? One that will not be around for much longer?” “I have walked in the wilderness. I havewalked in the past. Shall I just look at the elephant? And irrespective of his size, let him go?” Once more, further away, the hyena called into the night but now no one heard him.

The hunters, two trackers, a game scout, the professional hunter and the American, woke up stiff and cold. They drank no tea. They packed their sleeping bags, wiped the dew from their rifles and began to climb into the Zambezi Valley escarpment on the tracks of the bull.

It was four o’clock in the afternoon when they saw him for the first time. At ten o’clock they had stopped in a densely wooded thicket that smothered a small clear spring way up in the hills. The elephant had spent time in this glade and had fed and rested there some time during the night. The hunters had eaten the cold boiled eggs and some bread and then they too had pushed on, more carefully now, as the heated wind was beginning to whirl and eddy. Nomzaan, the number two tracker, saw the bull first. He was a long way off, still moving. He was moving slowly, but was moving none the less. The hills of the escarpment are quite open, mostly seas of gently undulating red brown and yellow grass. The trees are sparse and only thicken up in the streambeds and down along the base of the hills, so it was easy to see the tusks of the bull elephant. The two trackers, in unison, uttered “Hau!” while the professional hunter whispered “My God!” and the American and the game scout said nothing.

This was one of the few. This elephant was over seventy years old and must have lived many of those years in the protected National Park areas. But an old bull like this cannot stay in one place, he is compelled by something, some ancient urge, to walk the old elephant roads and visit far away swamps in which his father and grandfather before him had submerged their old grey bodies. He has escaped poachers, landmines and hunters. He has seen everything there is to see in the African bush. He is a living monument to old unspoiled Africa. He is nearing the end of his days.

“My God, he is the biggest elephant bull I have ever seen – his tusks curl into the grass – he’s a giant! He’s got to be near a hundred!” “A hundred pounds? each side?” The American was incredulous. “Yes! It’s too far to judge, I’m getting carried away! But he is the elephant of ten lifetimes. Nomzaan! The wind!” The trackers checked the wind with their ash bags. The government game scout walked up. “What is it? You see the bull?” asked the professional hunter. “I see him Sah. But the boundary of the Sapi is very near. The elephant is going back along the escarpment to the Mana. We cannot hunt in the Sapi”.“Yes I know, the boundary is near, you are correct. But I believe the boundary is on that small stream, the Silazi which is still ahead”. The scout said nothing.

The elephant was now nearly out of sight, heading west over a ridge, toward the Sapi. The hunters had new energy now and they dropped down the rough hills to the north. The breeze was coming off the escarpment from the south and eddying dangerously west, and the hunters had to try to circle around downwind from the bull’s chosen path.

It was a frantic, sweating half hour and the hunters dropped their backpacks in the shade of a mahogany tree and went on, carrying only their rifles and their water and once more, they saw the elephant. But still, he was moving. He was close to two hundred and fifty yards away, walking slowly through the sea of grass. The hunters conferred. The professional hunter’s face was tight with anguish. “We have to run, that dark line of trees is the Silazi, our boundary. We have to run like hell.” They ran. The hills in the Zambezi Valley are strewn with cannon-ball sized rocks and they are ankle twisters. The American was the first to go down but the others dragged him up and on they went. Noise was no longer a factor. They had to catch the bull before he crossed the boundary.

When the group came panting and wheezing up to the crest of a small ridge where they had last seen the bull, they began to search frantically with binoculars but it was the game scout who saw him. The elephant was still ambling along, slowly, but surely, below the hunters about one hundred and fifty yards away. The tall, gaunt old bull was about forty yards away from the Silazi, his head down, pushing those curved ivory columns along in front of him as if concentrating on keeping them in line, obedient, out of the stones and dirt. The professional hunter grabbed the double-barrelled rifle out of the American’s hands and thrust it at Nomzaan then be reached over towards the number one tracker, Uboyi, and took hold of the scoped .416 and pushed it into the hunters chest.

“Take him, take him! In the lungs! Lean on this anthill here! Come on! Take him, I’ll back you up!”

The American scuffled onto the anthill. He was shaking. His whole body was shaking. He looked through the scope and saw the giant, saw his longivory poles and saw his long thick slow-motion legs. Time slowed. Swish, swish, swish went the legs. Flap, went the ears. Swish went the legs in the American’s throbbing skull. His breathing slowed, the hours of campfire talk echoed hollowly in his head.

“Elephant hunting is a hunt of the legs and the heart -you have to walk him, you have to track him and walk him and find him.” “Elephant hunting is not shooting. Elephant hunting is endurance, and a matter of the heart!” “You find him, and you go into the bush for him. You get close, then you snick the safety off your double and you get five yards closer! You can smell him! You look up into his deep red-brown eye, and knowing now, that he will kill you, you kill him.”

But he looked now, over his high-powered .416, through the scope at the great bull as he left the grass angling for the stream. Swish went the great legs in the scope. Swish, swish, swish.

This book is a book for hunters. It is not a book that has been published in the hope that pro-hunting argument will reach out there to the anti hunters. There are numerous papers which have been published which argue the hunting case far more eloquently and completely than I could. So this chapter has not been cobbled together in order to drag out the well-known reasons why hunters hunt. I have included it in order to try to address the questions of ethics applied to hunting leopard by several different methods. But as can be seen by the story of the elephant hunt above, one thought, or one statement, or one answer, can, and does, lead off to another question and another unexpected branch in the stream, and it helps to illustrate one thing – that ethics are dictated by many different circumstances and traditions and cultures. We may not all have the exact same feelings in one particular situation as somebody else might.

Would you have shot the great elephant?

To state the obvious, ethics are involved every day, in every walk of life, in business, in war, in school, in marriage, in sport – the examples are endless. You don’t cheat at cards, you don’t pick up your golf ball, you don’t shaft your partner in business – ethics mean the relating to, or treating of, morals. Every hunter knows the black and white of ethics pertaining to hunting – it would be pointless to list them here. The debate, or questions which I feel compelled to address, are the “grey areas”. More specifically, the grey areas concerning hunting leopard.

The elephant hunt brings home what I mean by the “grey area”. Is the American hunter legally allowed to kill the elephant? Sure. Would you and I, would most of us kill this elephant? Sure we would. It is legal, it is a once in- a-life time elephant – you have worked like hell to come up to him, you deserve him, plus, you will be killed by your professional hunter if you don’t take the shot. But, isn’t there also that sneaking, stubborn, righteous pride when you hear that he doesn’t pull the trigger? That he set himself certain standards, certain ethics, that he would hunt elephant by? And shooting a twelve-thousand-pound animal at a hundred and fifty yards with a scoped .416 failed these standards.

Every one of us is different, and although we may agree, in most cases, on the black and white areas, we have to respect that our feelings or perceptions when confronted with the grey areas, may differ from person to person. So we approach the issue on ethics pertaining to leopard hunting. Hunting leopard over bait, hunting leopard at night with the use of a light, and hunting leopard with hounds. These are the three main issues. The ethics of hunting leopards with hounds is covered in the chapter “Enter the Hounds” so I will not address it again here.

Safaris in Zimbabwe are operated on three types of land designation. Big game government concessions which are owned and managed by the government, Communal Lands, which are also government owned, and finally, private land.

Big game safari concessions, like Matetsi in the northwest and Chewore in the far north, in the Zambezi Valley, are put out to auction every five years or so. The safari operator who wins the auction gets to operate safaris on these areas. These areas are land which has been set aside solely for the purpose of safari hunting. They are wilderness areas. No people, save those connected with the safari operation, live on this land. These areas are closely controlled by the Department of National Parks and Wildlife as they bring significant amounts of foreign currency into the country. Leopard, and in fact game in general, live out their lives in these areas largely unmolested by humans in the way which nature intended. On the smaller concessions, like Matetsi, where each unit or area is about eighty thousand acres in extent, the influence, or effect of man, is more pronounced, more intrusive for the game, than in big concessions like Chewore north, for example, which is nearly half a million acres. But when compared to communal land, or private land, even these smaller concessions are “unspoiled”.

Because of this absence of human activity on concessions, leopard behave in a very similar fashion to those which live in National Parks. They are not purely nocturnal. They move and hunt and carry out life’s functions in daylight hours as well as the night. Because of this, in the pursuit of “fair play” or ethics, you cannot hunt at night on a government area. There is no need to really. If you work hard and do your job correctly, and of course, receive your allocation of luck, you will draw a leopard onto your bait in the daylight. But I should make it clear here that it is no walk in the park. Any, and all leopard hunting requires skill, determination and self-discipline.

Communal land, once known as “Tribal Trust Land” is similar to what Americans know as “Reservations”, where the Native Americans have been allocated land so that they can live in their traditional manner. And so it is in Zimbabwe. The communal lands are where most of the population live in their traditional rural way. Communal lands vary greatly across the country. Some are more amenable to coercing a living from the soil than others. Some are closer to the main centres of commerce and communication than others, and some are harsh areas of dry bush land way off the beaten track, often butting onto National Parks and safari areas. These less-populated, more remote communal lands often have both resident and transient game populations which vary greatly from area to area depending on human activity and weather patterns. The people who live in these areas often suffer from the attentions of elephant in their hard-won crops and predators killing their goats, sheep, cattle and donkeys. In Zimbabwe, a successful programme called “Campfire” has been implemented and these projects have greatly assisted the rural people. They have protected and enhanced game populations and they have helped bring foreign money into the economy. Campfire is an acronym for Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources, and it deals not only with wildlife, but other natural resources like timber. With these Campfire projects, some of the money paid by safari operators and by foreign hunting clients, is ploughed back into the community. The theory is that if the local rural people realise some material benefit from this controlled hunting, then they will curb their poaching activities and husband the wildlife.

But wild animals, especially leopards, live a different life on these communal lands than their brethren do on the concession areas. The predators – lion, hyena and leopard – because of the human activity, have become almost totally nocturnal. It is a situation which prompts some thought. In the more remote parts of Masailand, in Tanzania, the amount of human activity is probably similar to that in the Zimbabwe communal lands. But in Masailand, the predators are not only nocturnal, they are active during the daytime too. As long as they do not molest the Masai livestock, the Masai leave them alone to live out their lives as nature intended them to. This has been the status quo in Masailand for hundreds of years. The Masai tradition is to live happily as neighbours with the wildlife. They do not eat wild game meat. But in the Zimbabwe communal lands, game has been persecuted for many many years and the animals know that the people want them in the pot. They are wild and leopard here very seldom move around in the daylight.

The game laws regulating hunting on these communal lands are different from those that are in effect on government concessions. Communal lands are treated in many instances like private land, and what is pertinent to this essay on leopard hunting, is the fact that one can hunt at night and one can use artificial light in these areas.

So much for the laws and regulations. What about the ethical considerations of private land leopard hunting? We have already pointed out that leopard, because of their predations on livestock, are going to be killed one way or another. That is not a matter of ethics it is a matter of survival. If you farm livestock in an area where predators live, then sometimes you are going to be confronted with the problem of dealing with an animal that has killed your livestock. And, sadly, in Africa, this means, ultimately, the end of all resident predators on all farmland. The first to go in so many areas in Southern Africa, were the lions. You cannot farm cattle in a lion area. The lions cannot resist eating cattle and in the last sixty years or so they have been just about wiped out in all cattle ranching areas. A sickening situation existed for many years up at the Matetsi/Hwange area in northwest Zimbabwe. A cattle rancher ran his cattle along the Matetsi safari area boundary and over the years shot literally hundreds of lions and lionesses “protecting livestock”, and this, coupled with unadjusted large lion quotas on the concessions, badly damaged the lion numbers in this part of the country. In 2005 the Department of Wildlife finally acknowledged the problem and cut the lion quota, and hopefully the situation will improve.

Leopard, although notorious livestock thieves, are not as one-dimensional in this pursuit as are lions, as they are able to “make do” on a much wider variety of game than lions are, and being such adaptable creatures, have been able to survive in areas where the last lowing calls of the lion cannot even be remembered.

People who have not hunted leopard on private land, or people who know little or nothing about hunting leopards on private land, often believe, erroneously, that shooting a leopard with the aid of a light is easy. They have heard, or read, or been told, that the leopard is blinded and freezes, deerlike, in the light. The only way to find out the truth of the matter is to seek information from those who know. It is not reasonable to form an opinion on hearsay. I do not want to sound dictatorial here – everyone has a right to their own opinion – I am saying that it should be a researched, or well-informed opinion. It should not be based on something said or bandied about by someone who is not qualified to dispense advice.

Fifty percent of our leopards which are successfully drawn to bait during the season, are either completely missed, wounded, or escape with no shot having been fired! And this is from double-rest sandbags at one hundred yards! If it is so easy to shoot a leopard at night with a light why are these animals wounded, or missed? The reason is it is not easy at all. The hunter is nervous and the leopard does not always present a clear easy shot, and does not “freeze” for the light!

This does not even take into account the enormous amount of work, and tactics that have gone into enticing a big leopard to come into your bait in the first place! So there is nothing “easy” about it! This whole book is about the cunning nature, the awareness, the contrariness of private land leopard, so it makes no sense to repeat all of that in detail here.

For a leopard on private ranch land to come into your bait while you are waiting in the blind, you have to be silent. You have to possess serious self-discipline you cannot sniff, or cough, or snore, or go to the toilet. You have to move gently and silently, and you have to do without your normal amount of sleep and you may have to spend more than a dozen nights out in the cold bush, away from camp. No fire, no shower, no servants, no hot meals or cold beers. You have to shoot well under difficult unfamiliar circumstances. You may do this kind of safari several times before you are lucky! You may spend gut-wrenching amounts of hard-earned cash before you finally run your shaking hand over that beautiful silky skin. There is no free lunch in hunting educated leopard on private land and anybody who says it is unsporting or unethical, has not tried it and is badly misinformed.

Part of our understanding, or definition, of hunting ethics seems to be grafted around how easy something is. Consider this: One client returns with his guide to camp after a hard day out in the bush. “Damn, them critters in this area are spooky, damned wild, huh?” The PH replies, “Yes, they’re wild animals. They’re not constrained by fences, or anything else, they’re persecuted by lions, leopards, hyenas, cheetahs, wild dogs, poachers and their dogs, and of course by us hunters. They’re not tame, we have to hunt these animals, really hunt them. We have to get the wind right, and catch them unawares”. But the client is unhappy.

A client, on another safari, returns home to the States and is recounting his hunt “Well, it wasn’t really hunting, the game stands there looking at you, you drive up, select the one you want, and shoot it. It was like a zoo!” This fellow, too, is unhappy.

So the point here is that hunters want things to be difficult, but not too difficult so that they can feel that the animal has had a fair chance. We are back to the “grey area”. What may seem good or fair for one hunter, may be unacceptable to another, even though it is legal.

South Africa has been plagued in recent years by the “canned lion” factor. This is the story. Lions are bred in captivity and sold to foreign hunters to shoot. Sometimes the animals are shot in a small sized pen. Other times they are shot in a “large” pen. Sometimes they are released immediately before they are shot into the “large” pen. Sometimes they are released a day, or a week before, into this pen. Sometimes there is a game played by the safari operator and the client. The client knows that the lion is not a wild free roaming animal. He knows that it is has lived its whole life in a cage. But the operator spins him a yarn about how this bad old lion has forced its way under the game fence into his property and is now a marauder, killing the game on his farm. “The Lion” he says, “has probably come from the Kruger National Park”. The operator and the client play this game and pretend that they are “hunting” a wild animal. This way their “conscience” is clear. The client goes home with his trophy and bullshits anyone who wants to listen, to the story about his wild lion, and the operator goes home with the client’s money. Everyone is happy. But this practice received quite a lot of bad exposure and certain restrictions were imposed. The enclosure into which the lion was released had to be of a certain size and the animal had to be released a certain number of days before being hunted.

One thing surprised me during the whole “canned lion” saga, and this was the number of clients, “hunters” who were quite happy to carry out this type of hunting! The biggest association of hunters in the world – Safari Club International – changed their record books so that “record” lion shot in South Africa would have their own separate category so that they did not “taint” and unfairly compete with lions that had been hunted in a free roaming, wild state, but business went on unabated. I, personally, know of several high-ranking personalities who “hunted” these South African pen-bred lions! When this lion rearing, for hunting purposes, came under pressure, the breeders formed an association and took their case to the Department of Wildlife saying that they were providing a substantial number of jobs and they were bringing a significant amount of money into the country via the hunters and more importantly, they had legally been given permission by the government to operate these predator breeding businesses! In August 2006, the Professional Hunters Association of South Africa (PHASA) issued a statement saying that they unequivocally were against this practice of shooting pen bred lions, and would take action against any of its members who were involved in it.

So here, once again, we have a situation where something may in fact be legal, but ethically, it is wrong, and as hard as it is to believe, many so called “sportsmen” or “hunters” are purchasing these hunts!

Recently in the Orange Free State province of South Africa, the Department of Wildlife made serious efforts to try and clean up this ‘canned’ lion hunting and they laid down restrictions governing how large an area had to be in order for a lion to be hunted, and rules were made that ensured that the lions were ‘free roaming’ and self-supportive for at least 6 months before they could be taken. These lions could not be baited and they had to be hunted on foot. A wildlife officer has to accompany all lion hunts. A step in the right direction. Several wildlife experts actually came to the defence of ‘canned’ or, more accurately, ‘farm-bred’ lion operations saying that if they were shut down, the hunting pressure on the few remaining wild lion areas in Africa would be devastating. So once more we have a grey area.

Hunting a pen-raised lion which has never killed its prey, has never raised a snarl, or a claw in anger, is pathetic.

Hunting a lion in a 5000-acre game farm, on foot, where he has to hunt and kill his own food, and has a good chance to evade the hunters, is different. But is it ethical? Is it sporting? Once again, a grey area – personal choices. I had a client back in the early eighties who came on his first African safari and hunted buffalo and plains game. He was a likeable fellow and a competent hunter and we enjoyed a good safari together. A few years later l bumped into him at a hunting convention and he told me about a recent safari which he had undertaken in Botswana. One of the trophies he had taken was a leopard and I was interested to hear the story of that hunt.

The long and the short of it was that the hunters had cut some good-sized leopard tracks and followed them by truck. In Botswana there are large areas of sandy bushveld in semi-desert terrain where tracking cats, if not exactly easy, is quite common. A bushman tracker runs on the spoor whilst the hunters follow in the Land Cruiser. Eventually, in a successful hunt, the leopard is spotted when he breaks cover and is pursued by vehicle. When he has had enough and can run no longer, he turns and will sometimes charge at the vehicle. This is the kind of hunt which was described to me. I was quite surprised at this method of hunting and when my client saw the puzzlement on my face he said, “Well, it’s better than baiting – I wouldn’t shoot a leopard off of a bait!” So there is the issue. It is, what perception does an individual have of that particular situation, of that kind of hunting? Botswana enforces various limitations on the hunting of cats with bait. But some operators utilise the method described above!

Personally, I find that ridiculous. What skill, or hardship is there in shooting a cat from a vehicle? The fattest man on earth could do it. Of course the tracking that the bushman is carrying out is a thing of beauty, it is hunting in its purest form. If someone were to hunt on foot, with the bushman, and take a leopard, I would say that that would be the absolute pinnacle of cat hunting. I have done it several times with lion, but never with

a leopard.

Here is another example of a “grey area”, or rather a situation where things have been made “easier” to ensure that the hunt is successful: In the equatorial jungles of Cameroon and Central African Republic lives one of the most beautiful, elusive and sought-after trophies in all of Africa – the Bongo. Traditionally, until fairly recently, there have been only two ways that the bongo has been hunted. Firstly, by ambushing a salt lick or an open glade or swamp in the deepest, most remote piece of jungle that a hunter can get to, and secondly, by slow, painstakingly slow, “still hunting” or stalking. With the first method, the hunters usually build a “machan” or tree platform high up where they have a good clear view of an open area which they know a bongo bull frequents. The hunters sit on this platform enduring ants, mosquitoes, rain and cramping muscles in order to collect the orange ghost of the jungle. With the other method the hunter obviously has to be a man of the bush. He has to move silently, with the aid of maybe one pygmy, through the jungle, following tracks, or maybe just stopping, checking the wind, waiting, looking, and hoping for luck. Very, very difficult.

Unsurprisingly, the success rates on these type of hunts is very low. I had a client who had been on four bongo safaris and never even seen one! On his fifth hunt, he and his wife were sitting, exhausted, at the edge of one of the big swampy, grassy clearings found in the jungle when the wife saw movement about five yards away. Something was sneaking through the tall thick grass. My client raised his rifle slowly, silently. Out stepped a bull bongo! He shot it in the chest and that beautiful animal turned out to be one of the greatest trophy bongo ever taken! But as I have said, the success rate on these hunts was poor.

Some operators began to use dogs. The pygmies in Central Africa have packs of curs, similar to the cursed rural terriers of Southern Africa, but smaller in size. These dogs are skilled hunters and do not yap and bark before it is time to do so. The hunting party relies heavily on rainy weather. Without rain they are unable to find or follow bongo tracks. When it does rain, they are out looking for spoor as soon as the rain lets up. The tracks are followed by the pygmies until they feel they are close to their prey or until the bongo is spooked, and then the dogs are unleashed.

The yapping hounds bring the bongo to bay very quickly, and whilst his attention is focused on the dogs, the hunter must close in and finish him.

Success rates climbed fast.

Several of my leopard hunters have taken their bongo this way and I was absolutely amazed to hear this news. Some of these guys are huge, out-of-condition, indoor types who smoked like trains and could not walk quietly on concrete, let alone in the thick jungle! So once again, hunters have “made a plan” – they have found an easier way to get their trophy.

Ethics? Grey areas? Once again, it bears thinking about.

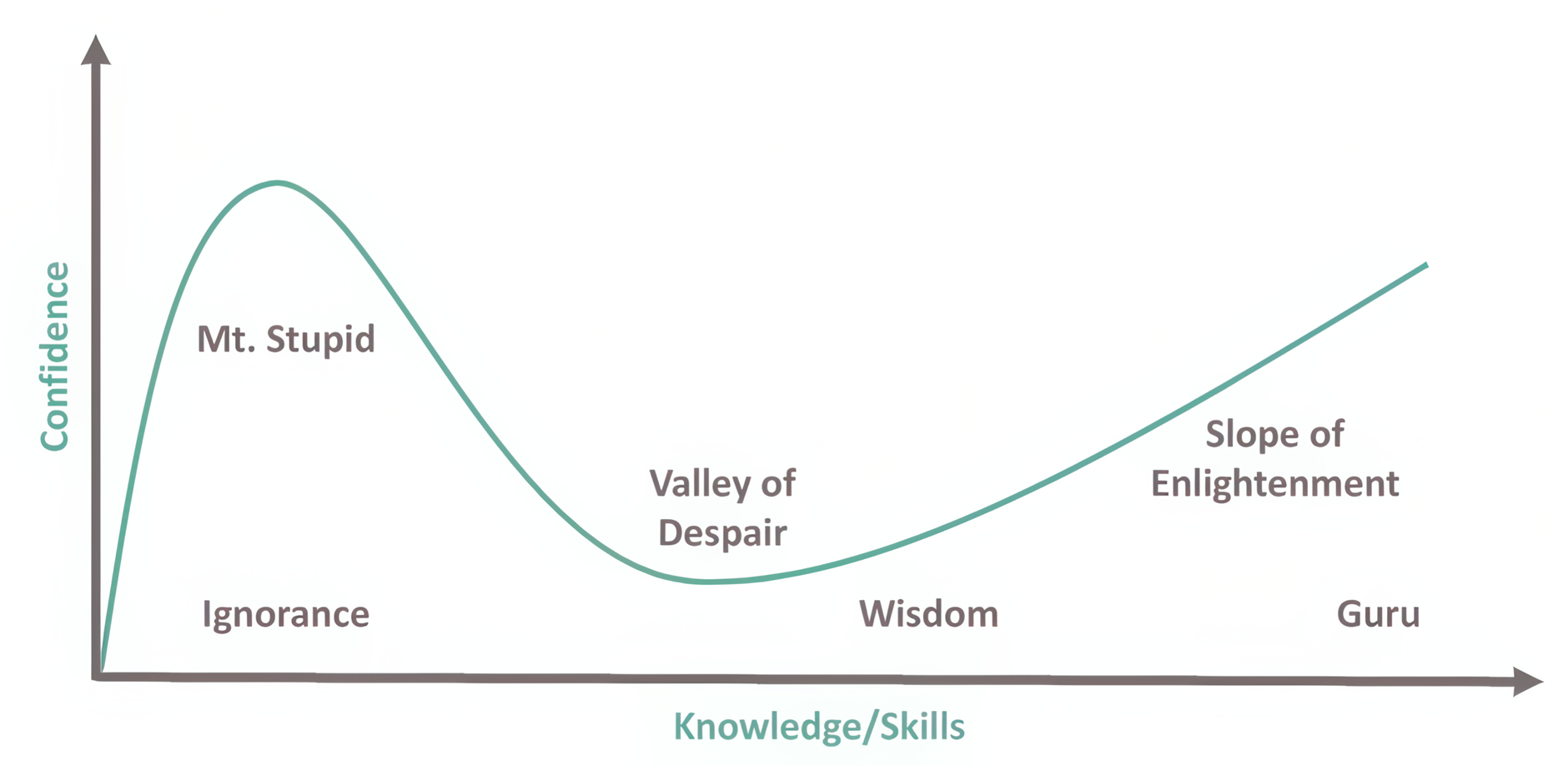

A safari operator I know well was faced with cries of ‘unethical’ when be defended hound-hunting of leopard. In his paper, written in answer to these cries, he made a point which I thought was an accurate assessment of what many, or probably most of we hunters subconsciously do. We ask ourselves a series of questions and if the answers to those questions are satisfactory, if they meet the level, or standard of fairness and honesty and acceptable morals which we hunt by, then we are okay, we are in the clear.

But we must not forget that we are all different, some of us see grey areas in the white, and some of us see them in the black. And unfortunately there are some out there who see nothing at all.