Wildlife Artist: Justin Prigmore

Shaped by the Wild

Born in Wales and now long settled in the Highlands of Scotland, the artist’s journey into wildlife art has been shaped as much by geography as by curiosity. Art was always a quiet constant in Justin Prigmore’s life, but it wasn’t until a formative gap year in Colorado that wildlife emerged as his true subject. While studying for a degree in Business Management, a visit to the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole proved pivotal. Standing among those works, Justin realised with sudden clarity that art was not simply a passion, but a calling he wanted to pursue for life.

At the time, a career as an artist felt far from practical. Yet the vast landscapes and cultural reverence for nature he encountered in the American West shifted his outlook entirely. Determined to ground his creativity in knowledge, he went on to earn a Masters in Environmental Science and Ecology. His early professional years were spent working in wildlife conservation, a path that not only supported him financially but also deepened his understanding of the natural world. Eventually, Justin’s dedication allowed him to transition into life as a full-time artist. Today, his work has earned international recognition, numerous awards, and a place in prestigious exhibitions, galleries, and prominent collections around the world.

Justin’s inspirations come from both the art world and the conservation community. During a ski season in Colorado, he encountered the work of wildlife painter Edward Aldrich, who was exhibiting in Vail. It was the first time he had seen someone successfully making a living as a wildlife artist, and the impact was immediate and profound. Although his ambition initially far outpaced his technical skill, that encounter set him on a path of decades-long learning and perseverance. Nearly thirty years later, at the Western Visions show at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, he finally met Aldrich in person and was able to tell him just how life-changing that early influence had been.

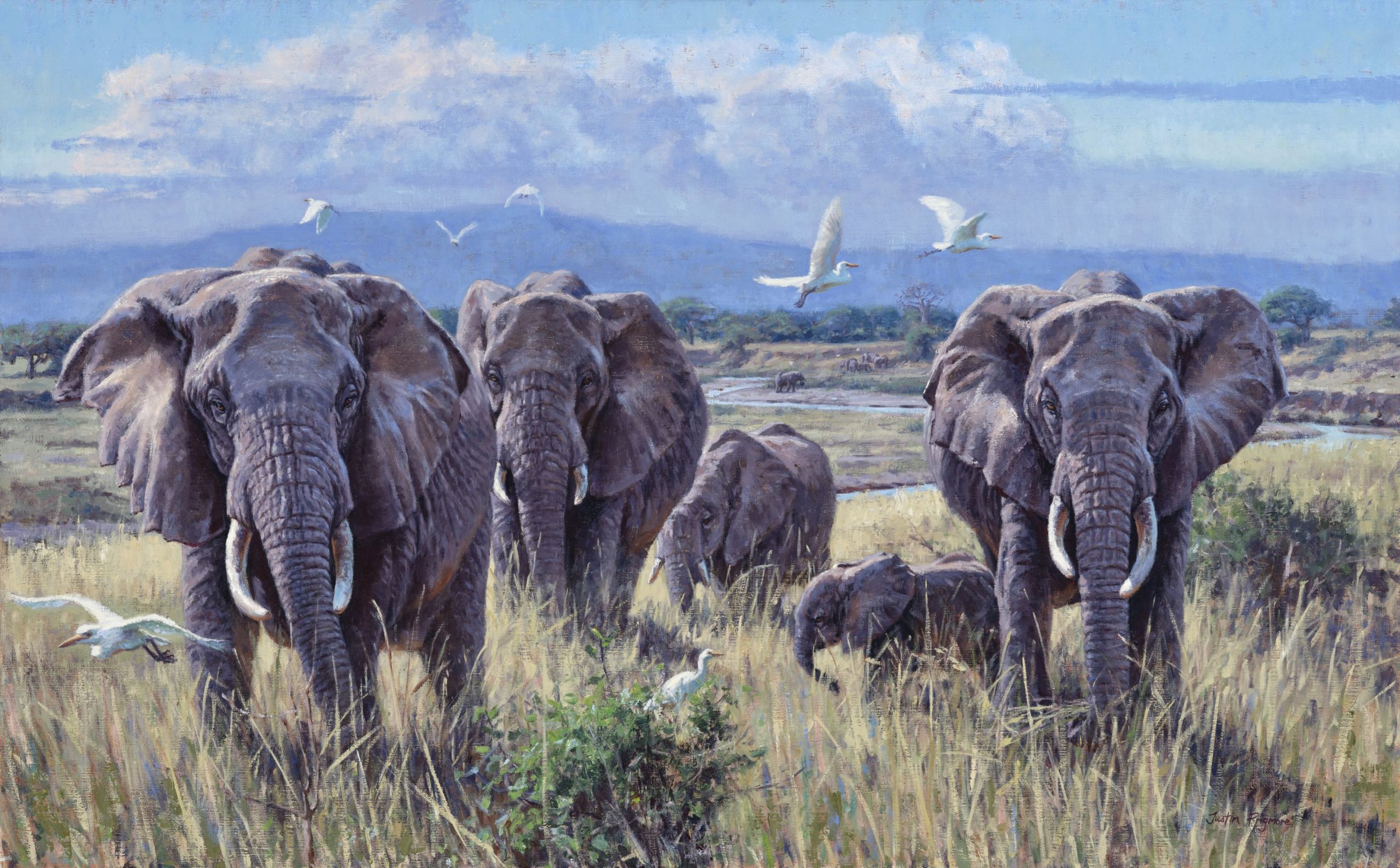

Another towering influence has been Robert Bateman. Through his books, the idea of an artistic life became not only attainable but thrilling. Bateman’s ability to weave together travel, wildlife, and art—moving seamlessly from a tiny wren to a monumental elephant—revealed a career that could be adventurous, purposeful, and deeply connected to the natural world. Today, Justin’s inspiration extends beyond any single genre. He is drawn to artists who can capture the essence and feeling of a subject without excessive detail, a quality he admires in deceased painters such as Kuhnert and Kuhn, and one he continues to strive for in his own work.

Equally influential were the conservationists he worked alongside early in his career. Their commitment to protecting wildlife reinforced his belief that art has a role to play in fostering connection, empathy, and care for the natural world.

Wildlife remains both his greatest passion and his greatest challenge as a subject. Unlike human sitters, animals do not pose, and the most compelling wildlife art comes from deep familiarity with its subjects—their behaviour, movement, and the environments they inhabit. That understanding can only be gained through long hours spent outdoors, often in difficult and unpredictable conditions, watching stories unfold in real time. While demanding, the process is deeply rewarding, and collectors often respond to the authenticity embedded in the work, recognising echoes of their own experiences in nature.

His favourite subjects are often shaped by place. Africa holds an enduring pull, with lions, elephants, and buffalo offering endless inspiration. The Highlands of Scotland, his long-time home, are equally close to his heart, their landscapes and wildlife woven into his sense of identity. More recently, he has been drawn back to the American West, a region whose powerful combination of dramatic scenery, abundant wildlife, and vibrant art culture continues to captivate him.

Hunting has also played a significant role in shaping Justin’s relationship with the natural world. He grew up in the UK bird shooting and fishing, influenced by his father’s enthusiasm for both pursuits. Later in life, he began stalking deer in Scotland, often through invitations from clients who wanted him to experience their land firsthand. Over time, this evolved into a deep appreciation for stalking—not simply as a hunt, but as a way of immersing himself in wild places and gaining a more nuanced understanding of animals and their habitats.

His career has opened doors to experiences far beyond the studio. On a recent commission in Florida, Justin took part in a quail hunt on horseback across a vast ranch. Despite not being a natural rider, he embraced the challenge and found the experience so rewarding that he has returned in subsequent years. For him, it offered a unique way to move through the landscape and engage with it on a deeper level.

Through hunting, Justin has forged lasting friendships with generous, passionate people and gained perspectives that continue to inform his art. Above all, these experiences have strengthened his connection to wildlife and the environments it inhabits—connections that remain at the heart of his work.

Bio

Justin Prigmore was born in Wales in 1974 and currently lives in the Scottish Highlands with his wife, two daughters and a labrador. His career has been shaped by extensive travel throughout the American West, Africa, and Europe. His paintings are exhibited worldwide and held in prestigious private and institutional collections. Through his art, he seeks to capture the essence of wildlife and place, fostering a deeper connection between people and the natural world. He has a MSC in Environmental Science and Ecology and as well as being a painter, has worked in nature conservation for organisations in the UK including the Cairngorms National Park Authority and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Born in 1974 in Wales,

Justin has exhibited his work internationally in prestigious juried shows, auctions and galleries, including with the Society of Wildlife Artists, the Society of Animal Artists and at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole. He has gained a reputation for dramatic and powerful large-scale paintings and his work can be found is some very prominent collections world-wide. Awards include the Liniger Purchase Award from the Society of Animal Artists, the Best British Wildlife Award at the National Exhibition of Wildlife Art and the winner of Birdwatch Magazine’s Artist of the Year. He is represented by the world-renowned Rountree Tryon Gallery and the legendary gunmakers John Rigby & Co. It is his association with Rigby that has led him to successfully showing his paintings at the Dallas Safari Club and at the Safari Club International in Nashville. These events have had a huge impact and demand for his work has steadily increased with clients from the US. Justin will be returning to the US this month to Atlanta and then Nashville with his latest collection inspired by his recent travels in Tanzania.