The Masai dwell in the area of the Kenya-Tanzania border that includes Mount Kilimanjaro, Masai Mara, the Serengeti, and the Great Rift Valley. Although current spelling is usually Maasai, with two ‘a’s, my friend Lekina, a Masai tracker, spells it with one ‘a’ and therefore so do I. They are a semi-nomadic tribe for whom cattle are the center of life.

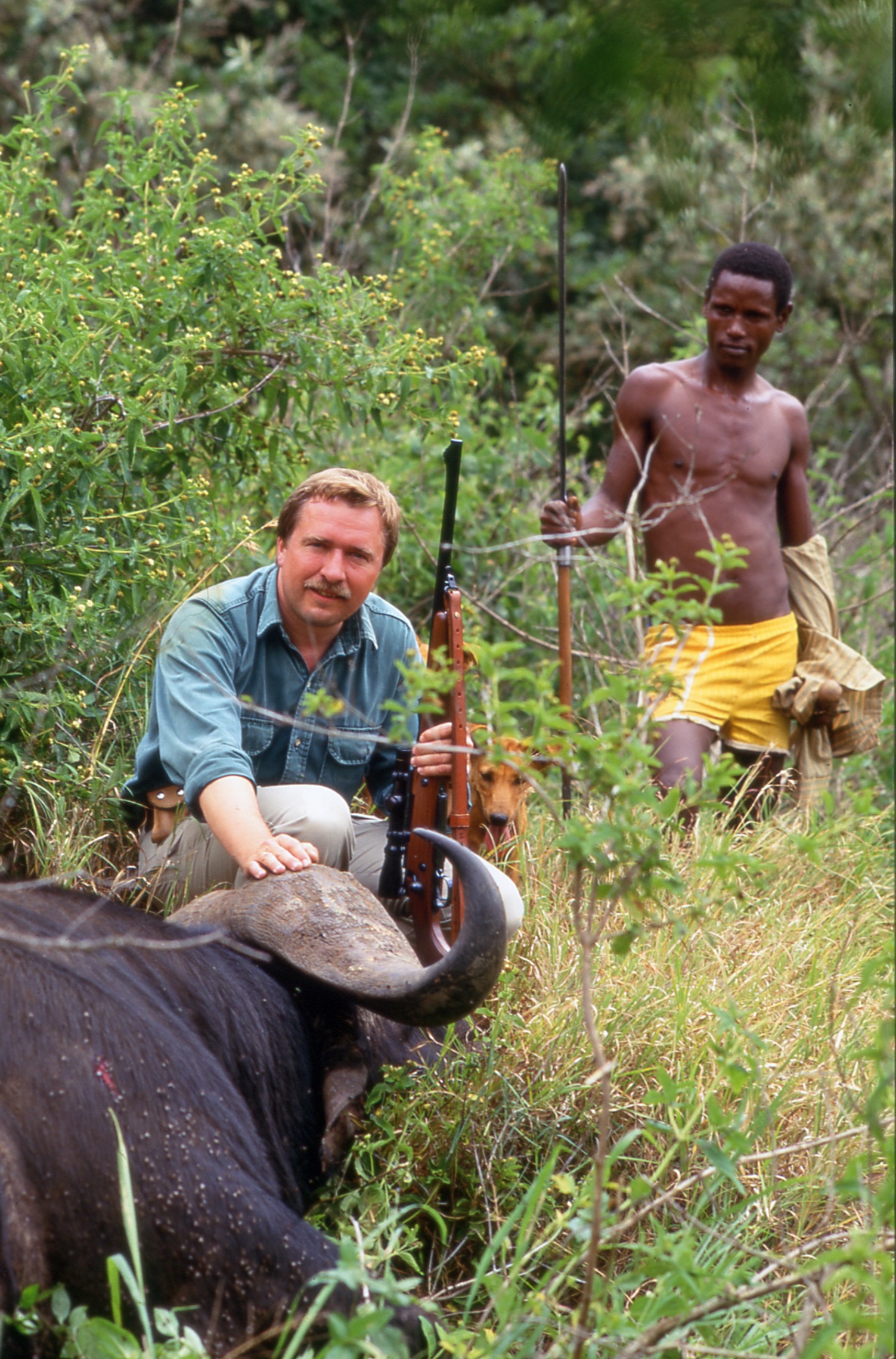

In 1993, hunting on Mount Longido, I had a glimpse of the true Masai character. Longido, like Kilimanjaro, is a huge, extinct volcano in the Rift Valley. We climbed up into the crater, where a few Masai families live in magnificent seclusion, and beyond that up into the rain forest of the high rim, there to hunt old, recalcitrant Cape buffalo, living out their brooding and solitary old age.

We were up the mountain for two days, then returned to our base camp. The local Masai headman came to visit, and reported that three transient lions had killed one of the Masai cows. Two of his men were guarding the carcass, and he asked if we could take our truck and bring in what remained. We agreed, and I was elected to ride shotgun up in the back, armed with a .458 Winchester. It was already dark as we wended our way through the thornbush, with a Masai guide tapping left or right on the windshield. It was a dark night — dark as only a night in Africa, complete with lions, can be.

As we reached a little clearing, our sweeping headlights caught the eyes of three lions in the bush, waiting and watching, and two young Masai tending a small fire. We wrestled the carcass into the back, the Masai climbed in, and we left the lions to their hungry disappointment. About halfway back, we came upon a young Masai herd boy, nine or ten years old, alone in the darkness with three donkeys, on his way to pick up the dead cow in the event that we, like so many mzungus, failed to keep our promise. The sight of him there alone, armed with only a miniature spear, made me feel a little foolish with my .458.

These, I realized, were the real Masai — not the posers for tourist cameras, the beggars at border crossings, the spivs from the streets of Arusha. Our young friend politely declined our offer of a ride. He had to take the donkeys home. They were his responsibility.

Twenty years later, I found myself in a small gathering that included one of my gun-writing acquaintances, a man who has been to Africa a few times, but never stayed long. All he has seen — or cared to see, for that matter — was airports and safari camps. Someone asked him about his most recent visit, and he took great redneck pleasure in recounting an anecdote about some Masai who, having some money, spent it on (of all the silly things!) a cell phone.

On the surface, this may seem of unlikely value. But when you consider that Masai settlements are widespread, in inhospitable country, and that most communication is on foot, a scattering of cell phones is the best time-saving device yet created. In fact, eminently sensible. Of course, you have to know something about the Masai and their ways to appreciate this, but all Layne ever saw through his bred-in South Carolina bias were the flies and the cow dung.

This is where the contradictions come in. In 2004, I was hunting Cape buffalo near Mount Burko. Not needing the meat, we gave one bull to the local Masai. In gratitude, the headman invited me to visit his establishment, where I met his senior wife and was invited — a great honor — to enter her house. It was dark and cool, scrupulously clean and neat, and the lady was understandably proud of it.

Beside a nearby mud hut, there was parked a shiny Mercedes. I asked who owned it. A neighbor, I was told. He had two sons. One he was raising as a traditional Masai; the other worked in Arusha, having gone to school and qualified as an accountant. Their father shrewdly deduced that having a foot in both camps would be a good idea. My contemptuous South Carolina acquaintance, I should add, does not and never has owned a Mercedes-Benz, although I do believe he has a cell phone.

On that same trip, I met my Masai friend Lekina, a tracker who absolutely loves carrying and shooting double rifles. He volunteered to carry my .500 Nitro Express, and wore it like a badge. When we later spent an afternoon using up the spare ammunition, he was like a kid at a carnival.

Two years later, hunting with him again, he accorded me the honor of inviting me home to meet his two wives, one of whom had prepared some of the traditional Masai curdled-milk for me. This strange concoction is mentioned in virtually every description of Masai life, and is usually described as a buttermilk-like beverage made from milk, wood ash, and cow’s urine. The Masai men carry it with them in the long gourds that are as much part of their uniform as their spear.

Sitting in Lekina’s neat mud hut with its thatched roof, I remembered how I had discovered, on my first poverty-stricken trip to Africa in 1971, how mud and grass huts are far more sensible for the African climate than any conventional European house. And yet, these are always mentioned to show how primitive African people are. In reality, they are very comfortable.

As for the Masai buttermilk (for lack of a better term) it has a taste all its own, but not an unpleasant one. I’m not sure I’d want to live on it, but if it would give me Lekina’s physique and stamina, I’d eat nothing else.